Wannabe White Girl, Part Two

This is part of the Maverick Monday series, where I talk about healing trauma (micro and macro) through the lens of a woman writer of color (that’s me!). Each week, I’ll share a personal story from my healing journey in the hopes that others will find comfort in knowing that they are not alone. I hope that by doing this, you can see that YES! Healing—true, lasting, deep healing--- IS possible and that you can thrive in your life, living as your most authentic self without shrinking from the world.

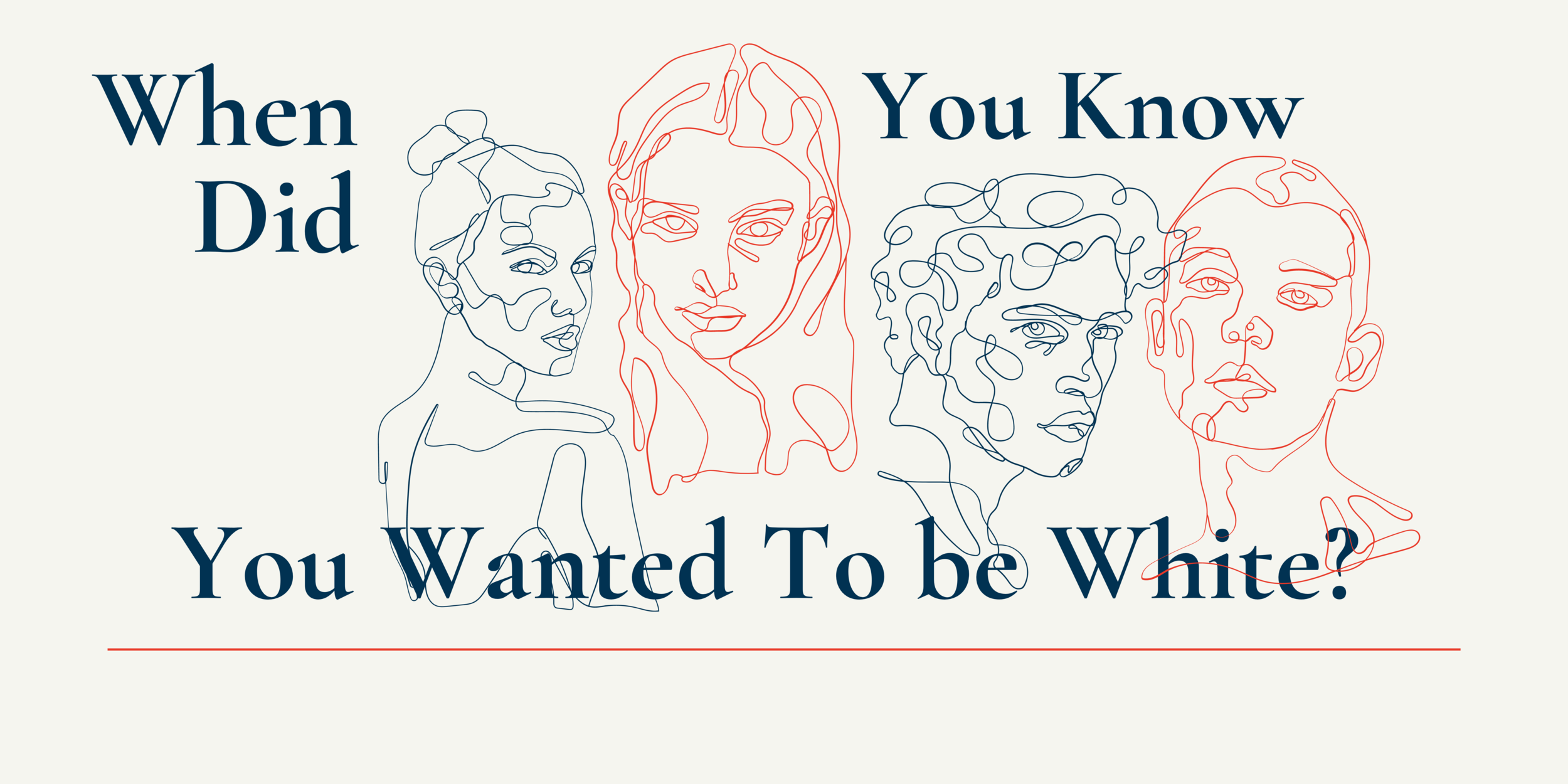

When did you know you wanted to be white?

A Filipina friend asked me this a few weeks ago. We had been talking about all kinds of things, from writing to healing to identity to activism to magic (that last part was me – haha). It was a good conversation. The kind of good that digs deep into the soul and feels nourishing while also nudging us to dive even deeper into the questions of our not-knowing.

When she asked me this question, I had to pause and really think about it. Did I always want to be white since I was little? Or was there a clear moment when I understood that to be white meant something meaningful (as opposed to insignificant)?

When did you know you wanted to be white?

*

Seventh grade.

We had just moved out of a town with a large Filipino population, where half of my classmates at the Catholic school were Filipino. The other half: a mix of white and non-white folks. And then we moved into in a mostly white community.

I’ll be the first to admit that I wasn’t the most astute of middle school kids. In fact, even though I was academically smart, I was pretty clueless, especially when it came to social cues.

The first day of school I felt bewildered. And not just because I was the new kid. I was one of three non-white students. One student was Chinese: Ann Chang. I immediately gravitated to her and we became instant friends. The other student, also new, was Black: Blair Underwood.

I recalled some whispers about him among my classmates, but nothing specific. I just sensed they were making fun of him. But I also knew in my gut (not my head) that they were being racist. A week later, he disappeared. The rumor was that his parents took him out of the school and he went somewhere else.

During that same first week, Mrs. So-and-So showed up in my social studies class, telling my teacher I needed to go with her. Was I in trouble? Why was I being taken out of class? I started to freak out on the inside, sweaty palms and a little shakiness.

She took me to this classroom where there was no one else except this other kid who talked a little funny. A kind of lisp. He was practicing his dipthongs. It turned out, Mrs. So-and-So wanted me to do the same.

“Touch the tip of your tongue to the back of your front teeth. And then say it: The. The three thighs. Feel it?”

Because I was a good girl, I did what I was told, but puzzled by the whole thing.

Who was this woman telling me to do things with my tongue? Why was I here and not in social studies? I wasn’t in trouble, I didn’t think. But somehow I felt like I was.

Later, during lunch, Ann asked me.

“Did they send you to speech therapy?”

“Is that what that was?” I thought to myself, what’s wrong with my speech? There’s something wrong with my speech?

“Yeah. I go on Fridays.” Ann seemed nonplussed.

And then it dawned on me. Ann went to speech therapy to get rid of her Chinese accent. And they sent me there because they presumed I couldn’t speak English correctly. They never tested me. Heck, they never even spoke with me in a conversation. I found out later that they didn’t even ask or inform my parents about speech therapy. They just sent me.

When my parents found out, they both took off from work (which was a big deal) and marched right into the principal’s office to set things straight, while I sat right outside the door. If my parents prided themselves on anything, it was my absence of any accent. Because they denied me to learn Tagalog –English only—I spoke flawless American English. And they were so proud. Sending me to speech therapy was a great insult to them.

When the office door opened, the principal, a nice lady with salt-and-pepper wavy hair, came out first. She knelt down in front of me and said: “I’m so sorry for the confusion. You won’t be taken out of class anymore. Your speech is just fine.”

I was halfway to white.

And in that moment, I learned first-hand that being white was the goal.

*

Fast forward fifteen years to the moment I meet a certain writer of color –now a long-time friend—who pointed out my acts of racial self-hate. To the conversation we had over breakfast one February morning in a diner near Washington Square Park as NYU students rushed to class and old ladies walked their dogs.

“Do you know how many Filipinas say that? Do you know that this is racial self-hate?”

I had just told this writer that I considered Filipino men to be like cousins, family. That the idea of dating them felt… weird. I couldn’t understand why this was racial self-hate. That’s how I was raised – to consider and address every Filipino I knew as Tita or Tito, which then, naturally, made their kids, who were my age, my cousins.

This began the painful unraveling of my wannabe white-ness. This began my journey towards healing the wounds of racism and of my childhood.

*